Voyage to America 1857

By Thomas Blackah

In writing an account of a voyage to a Foreign Country, the narrator ought to have had a good education, be well instructed, and have a good knowledge of the geographical position of the country which he has visited. But it is not the case with the writer of this small and short narrative, he having had only an imperfect education, being the son of a poor yet honest Lead Miner.

On the first of June 1857, I along with eleven others started from Greenhow Hill, a small village in the West Riding of Yorkshire, for Upper Canada in North America. The party consisted of my wife and two children, a brother-in-law and two children, a second brother-in-law and wife and three single young men. We parted from relatives and friends about 2 o’clock in the morning, we walked to Skipton, a distance of twelve miles, accompanied by my Father, two younger brothers, and a few other friends. We arrived at Skipton and took the railway train about eight o’clock in the morning for Liverpool, and bid adieu for a time to friends and relations ‘mid tears and feelings known only to those who have been in the same position.

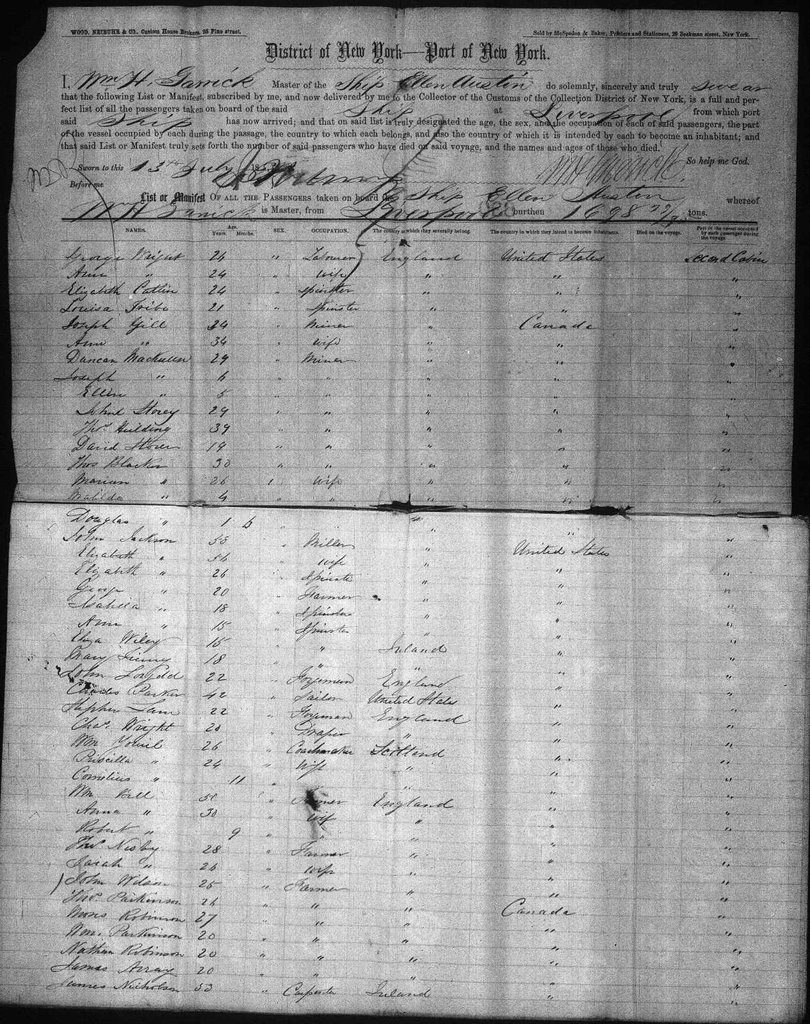

We arrived safely in Liverpool about three o’clock in the afternoon, and took our luggage to No. 5 Leeds Street, a Boarding Establishment, kept by a gentleman by the name of Howard. We found it a very comfortable place, highly recommendable to all Emigrants. We intended to take a passage to New York in a Steam Vessel (called the City of Baltimore). When we got to the Booking Office the Berths were all taken up, so of course we had to take another vessel. The first that sailed was a Clipper vessel, named Ellen Austin, belonging to the old Black Star Line. She was a large vessel commanded by Captain Garrick, bound for New York. We took a passage in the second cabin, but little did we know what we should have to endure on that vessel. We went on board on the 8th of June in the morning. When the hurry and bustle attending placing the trunks and boxes in a proper position had subsided, the officer commenced serving out provisions, but what was our surprise to have 7 biscuits, 1 lb weight, 1 lb flour, 1 lb Oatmeal, 1 lb Rice, 1 lb Peas, 1 lb Sugar, a small piece of tea, half a gill of vinegar, 6 potatoes, 1 lb beef, 1 lb pork for a week’s supply. The beef was either horse’s or elephant’s flesh. When it was well boiled 3 times it was not possible to eat it. They might cut it (with a deal of trouble) into small pieces so as it could be swallowed without much chewing. As for the pork, it looked as if it had been buried in the earth then taken out and washed (not clean) but about half clean. The rice and peas were moderately good, the flour was bad and dirty, the oatmeal very bitter. After provisions were served out we prepared to pass our first night on board a vessel. We had no lamp in our cabin, it was not allowed while the vessel was in dock. We slept very well the first night. When we awoke in the morning about five o’clock we had to go for our allowance of water; it was not so very good but we were forced to have it or ‘tithing; there was some crushing and squeezing to get supplied one before the other. We got about three pints each for a day. In the forenoon a steam tug came and towed us into the river. We cast anchor, the wind was so strong they durst not venture into the Ocean. In the afternoon a boat came with about 50 steerage passengers. When the hustle attending the arrival of the fresh passengers had subsided, a fresh one started up, in the steerage. The Officers caught a young man smoking below deck. They took him before the first mate -he ordered him to be taken on to the Poop and tied up by the hands to the mast.

We went to bed the second time and slept very well; we had a lamp in the cabin until about 10 o’clock and then the Officer appointed to look after the passengers came down cursing and swearing that if we did not go to bed he would take us on deck and put us in irons.

We were forced to comply to any request they chose to make to us. Next morning at 5 o’clock they came cursing and swearing if we did not get up they would pull us out of bed. We got up to a fresh bustle when they were serving out water. We expected starting into the main ocean on our voyage but the wind continued very boisterous so they durst not venture out. During the night a child was born on the vessel and one of the Mates was in irons for being drunk.

The next day a fresh company of passengers arrived and with them some orange women. They charged extra prices for their oranges and lemons and we found out for the first time that if we bought anything on board we should have to pay dearly for it. In the afternoon all passengers were called on deck and a search was made for anyone that was hid and wanted to go without paying. They only found one, a young man about 18 years of age; they took him before the Captain and kept him in hold till the boat returned. The passengers were all driven on the Poop and a man stood about the centre of the vessel with a list of all the passengers in his hand. He called out the names and another stout ruffianly man stood among the passengers calling out the names with a cane in his hand kicking and striking them forward towards the forecastle using all kinds of taunts and abusive language to them, the very people who were paying their money that he was receiving to support himself – and all this done in the port of the first shipping town of civilised England. After all was done the boat returned and took this brute in the form of a man, back with it together with the’ young man before mentioned, but before he went the mates bedaubed his face and hands over with tar and paint and they took him to Liverpool that picture.

On the morning of the 12th the steam tug arrived about 8 o’clock to tow vessel into the ocean, at the sight of which almost every face beamed with joy; we were all tired of remaining anchored in the river. About 600 human beings crowded within so small a compass, it was almost wonderful to think how we could live together 37 days. All was confusion and uproar while the seamen got the tug rope fastened to that little object that was to propel so large an amount of human beings, trunks, provision barrels, water casks (if they could call it water). It was that bad and noxious, although only a few days old when they were serving it out at one end of the vessel you might smell it at the other.

But it was wonderful to behold the little tug carry the vessel with such ease although scarcely a twentieth part of the size. It was a fine day and the scenery looked delightful as we came down the river Mersey. Behind was the thriving town of Liverpool, the mercantile metropolis of the known world. On our right was Birkenhead with its famous docks, with masts of vessels towering into the air for many a yard; further west was New Brighton with its fine park and beautiful buildings. Close to the water edge stood a noble lighthouse built on the solid rock and just beside it stood a stone Battery mounted with cannon that ranged the whole river. Before us lay St. George’s Channel the terror of all seamen in rough weather, and further west beyond the reach of his main vision lay the North Atlantic Ocean, where lay the bones of human beings without number.

The tug brought us as far as Holyhead on the Isle of Anglesey and from there it returned and left us to the mercy of wind and wave. We then bid farewell to old England expecting to see it no more for a time, if ever. We thought we had then got through the worst trouble attending emigration, but we soon found out we were only just going to meet it. As yet none of us was seasick but when the wind sprung up at night moderately brisk, then commenced the noise of people vomiting, some mourning, others praying, some cursing, some singing, laughing, talking, children screaming, the sailors singing their musical sea songs, although some of the sailors had good voices. If they had been properly trained they need not have been buffeted about on the ocean. Although they were niggers they were good natured and civil fellows.

When morning arrived the doctor came down cursing and swearing worse than a potter. If those who were seasick did not rise immediately he would drag them out of bed and what with vomiting and purging it would almost have suffocated a horse.

They were laid in almost every position imaginable; the deck was almost tenantless, there was no crushing and thrusting to the cooking galley as there had been the previous days. Very few wanted any meat that day.

We passed between the Welsh and Irish coasts but we were that distance of both of them we could discover nothing with the naked eye we could make anything of. Towards night the wind got right ahead of us so they were obliged to tack the vessel for the first time. We went to bed at night mid oaths and curses as usual. We had got quite used to it now and expected nothing else, nothing particular having transpired during the latter part of the day. About midnight we encountered a heavy gale and the vessel began rocking and creaking first rate, boxes begun rolling about, cans and bottles were rattling in all directions. Some passengers were thrown out of bed, men and women were shouting out in all directions the vessel was going to sink. Women and children were crying for help on all sides. The Captain and mates shouted out their orders, the sailors sung away at the ropes as if nothing were up more than common. We had a large crew on board. The Captain’s name was Garrick, the First Mate’s Kennedy, the Second Mate’s Ray, the Third’s Ledger, the Fourth’s Parke. There were three Boatswains the first Jones an Irish man, abused the sailors very ill, striking and kicking them without any provocation whatever; a Yellow Boatswain, a fine handsome looking fellow, could speak German and French fluently; and the other was a Black, a middle aged man possessed of some property in the States. There were near 30 sailors all Niggers, and 20 cooks, persons working their passages over and they were very ill-abused, scarcely ever having whole skin, especially their faces. I think if the Masters of the vessels only saw what the passengers and sailors had to endure (without they had hearts as hard as stone), they would have captains and mates with feelings of human beings instead of imps, for some of them would disgrace the brute creation, to be ranked among them. There is exceptions undoubtedly but they are very scarce.

The next morning was the time appointed for serving out rations and this produced a fresh hurry and bustle on the vessel, many a one having finished their allowance two or three days since and were eager to be supplied as soon as possible. It caused a deal of crushing that would not have occurred if they had sufficient provisions allowed, for according to the Bill of Fare on the tickets there ought to have been plenty allowed to sustain nature. If anyone had money to get more he had to pay an extraordinary price for it. A stone of flour cost 5 shillings English, and when they got it was only a ship’s stone. Currants and raisins were a shilling per lb. and they would not weigh more than nine or ten ounces, treacle about eighteen pence a pint (they did not weigh it), sea biscuits 6 for a shilling – they were so black and hard it was like eating tainted wood. Ale and porter was one shilling per bottle, port wine six, brandy five, gin and whisky four shillings per bottle.

There was only two cooking galleys for the passengers. The fires were kindled about 8 am. and put out at 4 in the afternoon, so there was not much time for cooking the little provisions we got. We were one day sat in our cabins very quietly talking about friends and home when we heard a crash in the air path into our cabin. It was the Captain’s child, a fine little boy about 5 years old. He had been playing on the Poop with a little wood horse (a toy) and the air path having been left open he accidentally fell through it, a distance of 5 yards. The First Mate came running down the ladder at full speed, happily the child had received no injury, only a little frightened. The Captain, in the heat of passion, swore the first man that left it open again he would shoot him.

In a little time after this when we had got settled, the First Mate and Jones the Boatswain, commenced beating a sailor for not scraping the masts right. They took both hands and feet to him, his face was so bruised they could hardly tell what it was like. It would have pitied the heart of a stone to have seen him if it was possible. After they had beaten him until they were tired, they sent him up again and kept him till dark at night without anything to eat; the poor fellow took it all very patiently.

Towards night a large quantity of porpoises came about the vessel. The sailors pretend to know what part the wind will blow from by the direction the porpoises sail. They say they always keep their heads towards the wind. But we prove this to be a fallacy many a time during our passage there and back. Whenever we were becalmed, if we saw any porpoises the wind always happened to rise just after, but it would have risen if we had not seen the porpoises. There is one thing that is true, when the wind is going to rise the sailors know, but any of the passengers could know the same. In a calm the water is very smooth and looks light coloured, but when the wind begins to rise it begins by ruffling the water and as the breeze gets nearer they may see the effect of the wind on the water by the small waves coming nearer and nearer and by stirring the water it makes it look dark coloured. This explains the mystery of the weather wisdom which the sailors pretend to have.

One night a young child died. It was buried the next night, and its parents were Irish, Catholics. A large company assembled round the berth of the bereaved ones, and spent the whole night in drinking and carousing one with another. They raised such an uproar singing, screaming, dancing and laughing, it was more like a madhouse than a place of mourning, but we were informed that it was a regular thing with those people on such-like occasions. This was carried on down in the steerage; if it had been in the cabin they would have had them all in irons before morning.

One day on the fourth watch Mr. Parker, the fourth Mate, and Jones the Boatswain, were on duty. Jones commenced beating the sailors as usual when Parker begged of him to desist and not abuse the poor men so, when Jones commenced beating him most shamefully, Kennedy the first Mate encouraging him to it. Jones cursed and swore he would pay him off for it after. It passed off for the present, only to be renewed in a tenfold more awful manner for at night about midnight there was such an uproar, oaths and curses accompanied by cries of murder. The first Mate and Jones made an attack on Parker in the dark, they nearly killed him outright. After some of the passengers had got to the scene of action, the first Mate swore he would kill him outright if he spoke another word. In the morning when it got light, Mr Parker appeared on deck with his face all cut and bruised most awfully. The Captain could not but know all the concern, for Parker was made Boatswain and Jones made fourth Mate in his place. What suffering has many a poor creature to endure on the ocean, if everything could be brought to light.

When we had sailed as far as the banks of Newfoundland it became very foggy so they kept one sailor constantly on the forecastle blowing a large horn to give warning to any vessel, which might be near, and another sailor at the bell, so that either the bell or horn was constantly sounding. But with all the precaution they can use, it sometime happened that two vessels come in collision. It was very foggy the second day and blew a strong gale from the south west, the sea was high, and the vessel was sailing at the rate of ten knots an hour, when the man on the look-out shouted out: “A sail on the lee bow”. Mates and men all rushed on the lee side of the vessel, and just when all became confusion the vessel clung to the weather side passing within fourteen yards one of the other. All the passengers that could get, rushed on deck to see what was up, but the vessel had disappeared again in the fog. This narrow escape brought down on the man on the watch almost a small volume of oaths and curses from the Captain and first Mate. Instead of thanking the Almighty for such an intervention of mercy, they appeared to be trying which of them could excel the other in awful blasphemy, but such was the degraded state in which those men had fallen into, nothing whatever could make them consider anything for a moment but devilry and wickedness.

The weather continued foggy all the way over the Banks. When we got to the other side we were becalmed almost every day, sometimes we just moved, at other times we had a dead calm. What agony of mind and body did we endure on that vessel, not knowing but we might be kept in it many a week, for the Pox appeared to be doing its work with redoubled fury as the air begun to be very hot in the day time, and at night it was so chilly and cold it was not possible to keep warm. Our cabins begun to be noxious and we could get nothing to clean them with. There were thousands of flies of almost all descriptions, they could not be kept out of our meat. One day we were all called on deck and the officers pretended to clean below deck. They found some members’ mugs occupied with excrement; they brought them out and cast them overboard. It was fine fun for the children, every fresh splash in the water brought forth fresh cheers from the younger fraternity of passengers who were very numerous, especially Irish.

We were becalmed one day, the sea looked white and smooth, there was not a wave to ruffle it, the sun was more than commonly hot, scores of little birds about the size and colour of martins gambolled around the vessel. It was really delightful, not a sound could be heard but the hum of human voices. The sailors were engaged tarring the ropes, there was no cursing and swearing by the mates, as was the case when the wind was up and brisk. Far away in the distance the water appeared ruffled and coloured, it gradually came nearer and nearer till within a short distance of the vessel it proved to be a shoal of mackerel. The place where they were appeared all life and motion and presently two huge whales made their appearance spouting up water many a yard high and then disappearing for a short time. They rolled their monstrous bodies over so that they looked like a large boat bottom upwards. They came right among the shoal of mackerel and remained among them about half an hour devouring them by scores and hundreds at a mouthful. After they had disappeared in the distance came two black sharks, the very image of cunning and ferocity. They kept at a short distance from the vessel for two or three days successively. They did not appear to mind the small mackerel, for they appeared to be abundant in the waters near the fishing banks; every day we could see them surround us on every side.

It was very hot one day and the sailors were all engaged tarring the ropes. When one of the oldest of them had finished his bucket of tar he came to the first Mate for more, so the uncultivated ruffian begun to make a game, as he called it, of him, but I dispute that a fiend out of Hell could have behaved so to a human being. He made the poor fellow put his hands into the barrel of tar and stir it up with them. He then made him take them out, take his hat off, put it in his breast, then he had the poor fellow’s tar brush in the barrel stirring it up with it and, when he was stuffing his hat into his breast, he rammed the tar brush right b between his eyes. He then made him wipe the tar off his face with his tarry hands and he commanded him to his work following him on the deck, dabbing his neck and face with the tar brush. The poor fellow was forced to take it all without saying a single word, if not he would have got well beaten and perhaps put in irons.

One day Jones the Boatswain commenced abusing one of the sailors; the poor fellow begged of him to desist, the first Mate came up at the same time he heard him so they both commenced kicking and beating him as hard as they could. They struck him with short pieces of rope right over his face and head till he had to lie down, and then they took their feet to him while he was laid on deck insensible. When they were satisfied of abusing him, they left him for dead. The other sailors had to carry him to his berth. He was so abused he was forced to lie in bed till the first night watch was called on duty. When they were called out it would have pitied the heart of a stone to have see their dejected looks. The Mates were more than commonly severe, they cursed and swore they would kill them all before morning and used all kinds of horrid language. When it got about dark they ordered the passengers below deck. We all thought there was going to be something up more than common for the first Mate walked about the deck with a large Newfoundland dog at this side, and the second Mate and Jones the Boatswain close behind him. After a while there was a rushing towards the cooking galley. Jones the Boatswain and the first Mate met the poor sailor who they had nearly killed in the day; they both commenced “full drive at him” with both hands and feet as usual. The poor fellow cried out “Murder” for all his might; the other sailors all made out of the way, expecting it would be their turns the next, for no one was safe on this awful ship. At the cry of “Murder” there was a rush of passengers on deck. The uproar it produced brought the Captain on to the Poop, he asked Mr. Kennedy what was “up”, the passengers roared out there was cruel work going on, and Mr Kennedy (after studying for an excuse) said: “Nothing, Sir, only a sailor fallen over the spar.” This seemed to settle all, for the Captain walked his way back again. After he was gone into his cabin, the two Mates and Boatswain came among the passengers enquiring who it was that interfered with them; if they could only make it out, they would put them in irons and keep them there, but no-one would tell them all seemed to be disgusted with them. The night passed away without anything more to do. The next morning the second Mate, Mr. Wray came into our cabin and appeared to be very communicative to some young women. When they made mention of the other night’s work he “blew it quite light” and said: “Black men could not feel it hurt the same as white men, they were like dogs and horses”. Here was a specimen of “good breeding”. What will the owners of vessels have to answer for when all things are investigated before the Bar of God, for employing and setting on such like brutes over the poor sailors. How will they meet the poor despised, abused, and slowly murdered creatures? What a sad catalogue of crime will there be published when “all things done in secret will be brought to light”. But no human mind can conceive it.

One night, an Irishman accused a German of “doing his business” at the corner of his “bunk”, so the officers and first Mate marched down into the steerage to fetch the delinquent before the Captain. When he had tried the case over, he ordered him to go and gather it up in his hands, bring it on deck, and cast it overboard. Of course he was forced to obey, so he landed on deck with a large handful; there were roars of laughter set up at him, but it was dark, which greatly accelerated the punishment of the “dirty beast”. He was a stout young man and one might have thought by his appearance he never would have been guilty of such a mean and dirty act, but how many; are there among the proud young fops of our country who are guilty of acts almost as loathsome?

When we were about 200 miles from New York we had a dead calm for many a day. There we lay on the water in that dirty vessel for nearly a fortnight surrounded by the most noxious smells that can be imagined, the sun almost shining perpendicular upon us in the daytime and our cabins almost filled with flies. It was in the month of July and our water had got so bad we could scarcely abide the smell of it. They had it in casks under the forecastle, and closets, we had to go every morning down into the low steerage for it. Sometimes we got over the shoe tops in excrement and urine when going to fetch it. How the poor creatures in the low steerage could live was almost a miracle; well might the hospitals be all filled with people with smallpox for there were about fifty with it when we cast anchor in the river near Staten Island. After we had lain in this position near a fortnight, and seen shoals of porpoises, and mackerel, and a large number of whales, besides two sharks which were our companions every day, the wind rather stirred and we soon discovered a Pilot Boat snaking towards us. How every countenance beamed with joy thinking that they would soon re-land, and then farewell to all troubles attending seafaring, but we were doomed to nothing but disappointments as will be seen in the sequel.

When the Pilot had been on board three days, we came within sight of a Steam Tug; it was soon alongside the ship and after a short parley between the captain of the Steam Tug and ours the “tow cord” was adjusted to the little thing and away it started with its huge load towards the New World. Every eye was stretched to its full extent to see land. After a while we espied land on our left; it was an island called “Staten Island”. As we came nearer to it, it looked delightful, fine green fields with here and there a tree in the middle of them, and the hedgerows bedecked with flowers of almost all colours glittering in the sunshine. It looked delightful; the buildings were painted nearly all colours. The island was literally filled with Halls and Mansions belonging to the nobility of New York, for Staten Island is to New York the same as New Brighton is to Liverpool, a place of resort and pleasure. We saw for the first time the splendid steamboats of the New World; they looked like floating mansions as they cut through the water at a swift rate. As we kept moving slowly and steadily up the river, fresh sights came before us, and with seeing nothing but water for about a month, our spirits were cheered with the sight of land, almost as much as the Children of Israel when they saw the Promised Land. We passed a large battery on our right, and about a mile further another on our left undergoing repairs and enlargement. When it is finished it will have upwards of 200 guns.

The Quarantine Doctor came on board the vessel, and when he saw the state we were in, he ordered the vessel to be anchored in the Quarantine Ground. Thus, when we thought of ending our troubles, a fresh one started up again, for we did not know what they would make of us, nor when we should be allowed to go onto land. A boat came for the sick and they took them right to the Marine Hospital on Staten Island. It was Sunday morning when we cast anchor in the Quarantine Ground, and we could hear the Church bells ringing on all sides of us, but there we lay in that miserable place surrounded by ruffianly fellows, and hearing nothing but oaths and curses, while we could see other people strolling about the river side, or skimming over the water in pleasure boats. A little boat came to us with fresh bread to sell, but we had to pay dearly for it, and we wanted water very ill. A few of us joined and bargained for them to bring us a barrel of fresh water; they would not bring one for less than 7s.6d. so of course we were obliged to either pay it or do without water. But before he left the vessel he told us he could not bring it till next morning. After he had gone away, we were soon through eating our fresh bread and although it was rather bitter it tasted very well to us who had lived on sea biscuits so long. But we were made to understand the position, viz. we were quarantined. No one but the Quarantine Officers were allowed to have intercourse with us.

The place where we were anchored was marked out with buoys and officers were stationed to see that none of us got away till the Pox abated, and also that no person came near the vessel with provisions but those set apart for it. In the afternoon a boat came to us with Spirit to sell. The officers (or police) who are always on the look-out soon espied it, beside our vessel. So off they set towards us with a boat and three men in it. When the two men in the boat that were with us espied the police boat coming, they were off as fast as they could row (for they were both row boats) and the other after them, and a fine race they had, the passengers shouting and laughing as hard as they could. But they overtook the trespassers before they got to land and took them prisoners, but it caused a piece of nice fun. After a while another smuggler came, and a fresh race occurred, which ended in the capture of the trespassers as before.

After this we had not the company of another boat that day, only he doctor’s. He told us we should all have to be vaccinated for the Smallpox the next morning. During the night a boat arrived from New York, and they smuggled a young girl out of the vessel unknown to anyone. Her brother, having heard of the vessel arriving and being quarantined, was determined to release his sister, which he accomplished, but being found out after he got six months’ imprisonment for it, and she was brought back to this Quarantine Ground and had to remain till the rest of the passengers got released.

About ten o’clock the next morning the boat came with the barrel of fresh water, and it tasted so well that we almost burst ourselves with it; we filled all our cans and bottles we h had and we were really worried with others that had not subscribed to it wanting to taste it. When Moses smote the rock in the wilderness the people could not be more clamoursome. Some of them actually kneeled down to lick up off the deck what was spilled, such was the state in which the poor creatures were in. After a while three Doctors arrived, and all were called on deck to be vaccinated, both men, women and children. It was like a sheepwashing; children were screaming, mothers trying to pacify them, men were sighing fearing to go through the operation, they were crushing and squeezing one against another, nearly all wishing themselves at home again, and well they might seeing what they had undergone and not knowing when there would be an end to it, for it was noised about we should have to remain in Quarantine sixty days. When the Doctors had left the vessel and we had just got down to our cabins, we got orders to lock our trunks and boxes and come up on deck. Thus, when we were just going to get something to eat, we were forced to leave it. They wanted to burn some tar in the cabins to quench the smells and to stop the infection. They kept us hungering on deck till nearly night, and when we were released the fires in the galleys were all out so we had to do as we could, without any cooked meat that day. We ate the fresh bread and drunk cold water to it. This being Monday, the day for serving out provisions, they served them out at night for one day; we got one biscuit, one potato and a small quantity of rice for the day’s supply.

They told us to h have all the trunks on deck by six o’clock in the morning, for the Steam Tug would come at that time to fetch us to the Quarantine Ground. We went to bed fully considering it would be our last night on that loathsome vessel; we did not care much what kind of a place they carried us to, so long as we got onto land.

But we were loomed to have one more disappointment before we got safe on to terra firma. Another vessel cast anchor alongside us, which started out of Liverpool the same morning that we did; it was called the Albert Galatin with near seven hundred passengers on it. They had the Smallpox on board, but it did not rage as it did on ours; they had towards 20 with it, we had 50. Early the next morning we were throng making ready for our departure. As soon as half past five o’clock, all the trunks and boxes were up on deck ready for the Steam Tug. Beds, and all kinds of pans, kettles, dishes, pints, bottles, Membermugs, were thrown overboard by scores at once. The water was literally covered with them. The children and younger end, were fairly delighted with it all. Many who had been clothes with rags, and barefoot, all the voyage appeared quite respectable this morning outside, but within would be almost empty, and underneath their clothes were scores and hundreds of living creatures; they could be seen parading the men’s coats and women’s shawls by numbers at once. It would almost make one’s flesh cringe on their bones to see them, they were quite ugly looking creatures, the large ones were very bulky about the middle or centre of their bodies but gradually tapered off towards the head and tail. Most of them had a dark spot right on the centre of the back, all the other parts of them were a light grey.

About six o’clock water was served out to any that chose to fetch it. A boy about fourteen years of age was going down through the hatchway to fetch some when he slipped and fell down through the lower hatchway into the low steerage. He fell with his head against a water barrel. They brought him on deck and laid him on a piece of canvas. The Doctor examined him and said he was dangerously hurt, having broken his skull and caused concussion of the brain, his nose was broken, he had a good many teeth knocked out, and they took him away to the Hospital.

About ten o’clock the Steam Tug arrived and commenced loading the luggage. It was four in the afternoon when they had filled it, and only about half the passengers with their luggage could get on at once. We expected it coming again for the rest, but we were informed it could not come till next morning. Nothing now remained for us but to spend the night as well as we could; we had not a bite to eat. And the worst was, as soon as the trunks were got up in the morning, the sailors were ordered to pull all the berths down and make ready for cleaning the vessel before she would be allowed to enter into port. Here we were with two children, one four and the other two years of age, not a morsel of meat of any kind nor a bed to lie down on. We had kept a little quantity of the fresh water we got the other morning, but it was poor support for n empty stomach. We asked the first Mate for something to eat for the children but the wretch did nothing but laugh at us. When the children wanted to go to sleep, we fetched two or three boxes down and took some of the clothes out of them to make a bed of, we laid some long boards across the boxes so they did for beds for the children and sittings for us. We got the night passed as well as we could, and in the morning the Steam Tug arrived to fetch us on shore. About noon we were all safely got on to the Tug Boat, and we gave a hearty farewell to that miserable vessel.

When we got to the Quay or landing stage, the women and children were all taken forward and the men had to stay and get the luggage to the Custom House. While taking the boxes off the boat one of them happened to fall into the water and it floated nearly a hundred yards from shore. A young Cornish man stripped himself and swam after it and brought it back. When we had got them all into the Custom House we were taken into the ground appointed for us, where the rest had gone the day before. We were guarded by officers all the way to see that none made their escape, for we found out we were now considered no better than convicts. When we arrived at the gates they were locked till we were all ready to pass through; the passengers who had come the day before were at the gates ready with water for us. They welcomed us with a loud cheer. When we had got through the gate in the Quarantine Ground we found it about an acre in extent, surrounded by a wall nine or ten feet high, and we were told that anyone that made their escape were to get six months imprisonment. After we had got settled a little we were all ordered to one end of the place and had to pass before the Doctor one at once to be examined. He told us there would be some meat for us in a short time. When it came it was tea and bread; we scarcely knew when we had got enough, it was forty eight hours since we had a taste of meat of any kind. The children, poor creatures, were fairly ravenous. They brought the bread in a cart in long square loaves about a foot long, six inches broad and four thick; these were cut into four pieces and thrown into hampers.

All the women and children sat by themselves on the green at one end of the ground, and the men at the other end. They were all arranged in rows, then there were two or three hamperfulls of tin pints brought and distributed amongst them, afterwards they came down between the lines with the bread throwing it in regular rotation all along as they came through. Afterwards came the tea, in large kettles or cans, and some female servants to serve it out. Many a time has the place rung with roars of laughter, when there has been scrambling among them for the bread which came towards them. There were young foppish gentlemen and ragged dirty looking creatures all dining together off one table, viz. the green sward.

After we had partaken of the tea and bread, we prepared for passing the night. The women and children were taken from among the men and put into a long wood building one storey high about forty yards long and eight broad. There were two doorways into it, one at the sound end and the other nearly in the centre. It was lighted by nine windows, eight in the front and one at the north or far end. There was a row of iron bedsteads placed up each side, with straw beds on them. They had grey horse sheets for blankets. Into this place the women and children were put to spend the night as well as they could. The men were put into a building three storeys high, which stood at right angles to the other. Into this place we were forced to lie down on the floor, there being no bedsteads for us. The first night we lay on loose straw laid on the floor the same way they bed horses, wrapped up in grey horse sheets. Many of the men laid in the open air on the bare ground, but before morning they were almost worried with mosquitoes, a kind of gnat, which is very troublesome all over the United States. It is about half an inch in length of body, long legs, and a large head. It is in shape nearly like a Ginnyspinner, its bite resembles the bite of a Clegg. There was also to be seen at night the “Firefly”. Numbers of these little creatures were dancing and looked like sparks of fire for an instant and then all appeared dark again. No sooner could you get your eyes to the place where they appeared, than all was dark, and another appeared in another direction.

Then morning arrived, we arose and got ourselves well washed in pure water which refreshed us very much, but before we got our breakfasts we had to pass before the Doctor, and it was nearly ten o’clock before we got any. When it came, we were all arranged in rows as usual, and we were ready half an hour before we got it owing to the women and children being served the first. Many a thought passed through my mind, as I surveyed that mixed multitude; if it had been possible, I would have given the world to have been set down with my wife and two children at the home we had left, but that happy time never arrived, as will be seen hereafter. If every one that intends to emigrate could only see the misery that they would have to endure, I am fully persuaded there is not one in a hundred would ever start with a family.

During this day, the passengers from the other vessel “Albert Galatin” came on shore to the same place where we were. This addition made our number amount to near 1300. We had to fast till they got all settled, and then they got served before us, so it got to be nearly night before we got anything to eat; we only got two meals that day. When we had got the supper over, we were ordered to a fresh shed at the north side of the ground. We had nothing but the bare ground to lie on. The other ship’s passengers took possession of our places where we lay the other night. When it set in dark, they commenced playing and dancing, just as if they were at a Country Fair. About midnight they commenced fighting and raised a regular row. The officers went in among them armed with revolvers and they took several of the ringleaders into custody. That night eleven young men made their escape out of Quarantine; they all belonged to the “Albert Galatin”.

The next day, the first Mate belonging to the “Albert Galatin” came to see the passengers belonging to that vessel. They showed their respect to him by carrying him shoulder high all-round the ground, cheering and waving their hats in all directions. This proved how well he had behaved to them on their outward passage. They were allowed to dance, sing, play, or do almost anything to keep up their spirits while on the sea. Their water and provisions were good, all the way, they were supplied regular and had as much as they could eat and drink allowed, so no wonder about them being so pleased with the first Mate when he came to see them. But we had a different scene presented to our view before night. Mr. Kennedy, the first mate belonging to our vessel “Ellen Austin”, came through the ground to see Jones the Boatswain who was with Smallpox. He got nearly through the ground before the passengers were aware who it was. When they made him out there was a regular rush towards him. The Germans drew out their large knives, some armed themselves with large sticks or anything they could find, and after him they went; no doubt but they were cursing and swearing vengeance on him if we could have understood them. The officers and Doctor had a deal to do to keep them from following him into the Hospital, but when they could not get after him they prepared themselves for his return. But in that they were frustrated for the Doctor got him conveyed through some gardens in another direction, and a lucky hit it was; if he had come the same way back as he went, he would have been lunched as sure as eggs are eggs. His behaviour towards the passengers (especially the Germans and Irish) was horrible; he was a real fiend in human shape. He had no more feeling for a human being than a stone; he had that wisdom about him to never try the experiment again.

The first Mate belonging to the “Albert Galatin” came every day. We thus passed on in misery and sorrow until the twenty second of July, when we got orders to make ready for our departure for New York. When the Doctor made it known, there was such a shout of joy raised as I shall never forget; every one of our passengers, men, women and children, followed him to the gates, cheering him all along, as far as they were allowed to go. He was a model of good nature and kind-heartedness; we never met with one like him wherever we went, for it seems to be a general trait in the characters of all the Yankees to be as big rogues and sharpers as ever they can.

After breakfast we started for the Custom House. The Steam Tug was ready for us; after we had got through the gates of the Quarantine Ground, we felt like convicts that had just got their liberty after a long term of miserable servitude, although we had not been kept in chains and forced to labour, yet we had been hungered to all intent and purposes. When we got all the luggage onto the Tug Boat and were nearly ready for starting to New York, the second Mate Mr. Wray and the yellow Boatswain came to the boat to take a last look at the passengers. Wray left the first amid hisses and groans from all parts of the boat, although he was not so bad as the first Mate, yet he had behaved very badly to the passengers all the voyage. When the yellow Boatswain left, he was cheered as far as he could be seen; all the passengers respected him, he was always civil and courteous, and he will be long remembered by all who knew him. As we left Staten Island we cast many a long look at it, there in the Hospital lay a brother with the Smallpox, and in the village adjoining the Quarantine Hospital was his dutiful wife, surrounded by strangers, not a person whom she knew to speak to, but she would not leave her husband, although she had two brothers and a sister going up the country whom she might have accompanied.

As we came towards New York we came past a little Island on which stood a large battery, mounted with large ordnance. We landed at a place called Castle Garden, a large circular building stood in the centre of the garden which had formerly been used for a theatre; it was a splendid building. There was a large number of emigrants in it, for they are allowed to stay here six days if they choose, and no lodgings to pay. They have to find their own meat, but they can go away any time they think proper. We had to get our names registered, where we came from, and where we were going, what age, and what profession or trade. There was some crushing and squeezing here again; all wanted to be forward to where they intended settling.

We had booked ourselves for Toronto, at Liverpool, by the New York and Erie Railway, so we had our tickets to present to Messrs. Holman and Wilkie, 27 Greenwich Street. It was close beside Castle Garden, so we had not much trouble to find them. When we got into Greenwich Street, instead of finding a fine looking well paved street, it was dirty and all full of jolt holes, but we did not stay long in New York. It was three o’clock when we got in, and we took the Steam Boat to Albany at five. The Steam Boat was a fine built, clean, and well finished off vessel. It looked delightful sailing up the river Hudson, it being a fine summer’s night.

As we left New York the river’s banks were very rocky, sometimes the rock would rise perpendicular to a great height, and here and there a small hut, built on the water’s edge. We had a band of music on board, composed of English men; they enlivened the scene very much. When we arrived at Albany it was eleven o’clock at night, so we could not see what sort of a place it was. When we came off the boat we were close beside the railway depot so we got our luggage weighed and got straight into the cars. (The railway carriages are always called cars by the Yankees.) We were all that night, and the next day till night came, before we got out of them; we passed a great many places but none of them appeared to be any way attractive. One place called Susquanha looked a pretty little place. When we arrived at a town called Corning (a miserable looking place) we were informed that we should have to stay there all night, and we were not sorry for we had not laid in a bed for forty six days, and the thoughts of a night’s rest almost refreshed us. Our luggage had to be out of doors all night, for there was not a building of any kind about the station to put them in. We went to a Lodging house, a wood building; judge what were our thoughts when we got in to the house, there were only a few chairs in the house, so we left the women and children occupy what sittings there were, and we were obliged to either stand or sit on the bare floor. After remaining about two hours in suspense, we got our suppers, which consisted of potatoes, beef, and tea, for which we paid one quarter dollar, the price we paid for every meal we got in United States. When we were ready for bed, they showed us to our bedrooms, and what was our surprise when we got in to the room we had to spend the night in, the rooms were all open one to another. There were door places between them but no doors in them. We laid on straw beds, their candlesticks were glass bottles, the candles were put into the bottle necks and the bottles were placed anywhere where there was room for them. However, there was plenty of air circulating in the place; we could see the stars through the roof. It was a wood building only newly built; it looked well at the outside, but within it was a mere pig cote.

We started the next morning on our journey, and rode till night. When we arrived at a large town called Rochester, we were informed that the train would go no further that night, so we should have to stay all night. When we had got our luggage on to the platform, we were told that it would have to be conveyed to another depot about a mile and a half off. We were soon accosted with runners belonging to different Hotels and Lodging.

One of them, an Irishman, was very troublesome, and would have no naysay but we should go with go with him; he told the women and children to get into his omnibus and he would take them free of charge. We told him to leave them at the depot till we got there with the luggage. After they had gone, an Englishman came to us and told us they had taken them to an Irish Hotel, and that he kept the only English Hotel there was in Rochester. We went with the luggage to the depot, and when we got there we found his words to be true, so we fetched them away and went to the English Hotel. It was called “Williams Hotel”, within a few yards of the Station where the luggage was. We found it a very comfortable place; the owners were a young couple from London. They had a good many well furnished rooms and excellent feather beds to lie on. This was the first night we had spent comfortably since we left England. It was a large brick building in a fine street right in the centre of the town. We felt ourselves at home. The master and mistress were very communicative, we learned from them that we had come out at a wrong time, for things were very dull in the “Canadas”. We passed a very comfortable night, and next morning we started on the Railway. We rode about seven miles and found ourselves on the margin of “Lake Ontario”. This is a large freshwater Lake, between Canada and the State of New York; it is about two hundred miles long and about seven or eight broad in some places. It has a communication on the north with the River “St. Lawrence” and on the south west the “Niagara” joins it with “Lake Erie”.

We were soon on board a Steam Boat that was in connection with the New York and Erie Railway; it was built like the pleasure boats at New York, having three decks. They are very comfortable and swift sailing boats. They burn wood for to work the engine with, and as soon as they had got in the regular supply they started across the Lake for Coburg in “Upper Canada”. We saw numbers of vessels crossing the Lake in all directions. After we had been on board a few hours, we were informed that we could have our dinners for one quarter dollar. We were quite ready for it, so we went down into the saloon and got one of the richest meals we had got since we crossed the Atlantic. It consisted of beef, potatoes, mutton, pies, puddings, tarts, fowls or almost anything you chose to have. The cooks were blacks but we did not mind much about that, for we found out that they knew how to cook as well if not better than white people. The saloon was a fine large room, exceedingly well furnished; there were in it three large glittering chandeliers, two large superb mirrors, a large quantity of elegant chairs, and numerous other costly articles. It was quite sufficient for any gentleman to dine in. When we wanted to drink we could go to the pump and pump as much as we wanted. It had a very good taste but was warm, it being a very hot day.

We arrived at Coburg about five o’clock p.m. and had to leave this boat as it came no further but returned back to Rochester. A boat would come from Kingston past Coburg, and we should have to embark for Hamilton we were told, but when it would arrive at Coburg they could not tell, but we must hold ourselves in readiness for it. So of course we got our luggage piled up on the quay, and went into the town. It was a pretty little place and we were told that everything was very dull. There was very little building going forward, as we had come from England to the Lead Mines near Toronto, we made enquires after them, but were told there was never such a thing heard of there. We went to a coffee house and got something to eat, and then went on the quay. It was a fine and when they got to hear that there was a company of emigrants arrived, they came to see us by scores. Everyone enquires where we came from; there were about twenty of us and we had all kinds of questions put to us. The natives were chiefly Irish, and by far the greatest bulk of them wished themselves in old Ireland again.

Footnote; This account by Thomas Blackah ends somewhat abruptly. In his original notebook there appear to be some pages missing, but what he did write has been faithfully “translated” and typed by Michael Blackah’s wife Pat.

(This is typed from the original written diary of Thomas Blackah, which is in the possession of Michael Blackah, great-grandson, of 9 Ashfield Grove, Whitley Bay, Tyne & Wear, formerly of Pudsey, Yorkshire. Typed October 1996.)

In a booklet Dialect Poems & Prose by Thomas Blackah of Greenhow Hill, published in the 1930s by Harold John Lexow Bruff, he writes in a short biography of Thomas Blackah that he was a restless man who could not settle down anywhere and in less than 17 years lived in 17 different houses. Writes Bruff: “He emigrated to the States, but found that he had been deceived by the emigration agent and soon returned with his tail between his legs. To justify himself apparently he wrote and circulated a description of his experiences, still extant, which is a terrible indictment of what was allowed on board the passenger sailing vessels in the year 1857.”

This is a fascinating narrative. My 4th-great-grandmother, 3rd-great-grandfather, and his siblings immigrated to America aboard the Ellen Austin under Capt. Garrick a few years later, in 1862. Thank you for sharing this.

Thank you so much for printing this story. My Great Grandparents came over on this ship in 1863. Makes their journey come alive.

Pat H

On November 10, 1857 my great great grandfather and grandmother arrived in New York on board the Ellen Austin. This was likely the very next trip. I never could have imagined the horror that they had to endure.

Thank you for posting this!