Biography of Thomas Blackah 1828-1895

Thomas Blackah, born and bred at Hardcastle, near Greenhow Hill, was a sweet singer, at best when he wrote in his homely dialect, though some of his poems in English are very graceful. The reason is riot far to seek because he wrote out of a full heart expressing with genuine feeling his love for the beauties of nature and especially his home on the Hill, which only they can fully appreciate, who have lived, there, close to the moors with ling and bent, the distant views rich in colour and with ever-changing light and shadows, the plaintive, moor birds and the whispering wind – in short, the Hill in all its moods – which he so vividly describes. Then he was freedom loving, with a high opinion of his station and calling, and of his fellow working men.

He was “A Working Miner,” as he used to describe himself, hailing from an old mining family, which had been domiciled for several generations in the district embracing the three mining villages of Kell House’s, Greenhow Hill and Hardcastle, the first being a very old hamlet referred to as far back as in William the Conqueror’s time and very likely even before that, as it was an important lead mining centre where we know, that the Romans mined the precious metal and that they had a summer camp on the Hill itself. Thomas Blackah loved what was fine and good, and detested what was ‘hollow and deceitful, a trait which the frailer of his fellow men in that small community resented when he took them to task and allowed his sense of fairness and justice, have free play, expressing his sentiments in scathing sayings and epigrams, often with a humorous point, which caused merriment and made the thrust the more telling. As for instance when Thomas was asked at the “Miners’ Arms” what his neighbour “Bonny Barker” was doing, Bonny having, much to the disgust of his fellow villagers, accepted the appointment as the local constable) the only man who up till then and since to hold an official position Thomas said, “Ah seed Bonny in t’back yard wey t’batoun, he war practisin’ stroakes, killin’ moock flees.” The joke was too much and Bonny gave up his baton and appointment.

Again he spared nobody if he thought they deserved reprobation. An uncle of his was a notorious slacker, suspected of stealing sheep off the moor and having set fire to his barn, which had been substantially insured. The suspected arson made Thomas’ restraint give way and he wrote an epitaph, which in biting sarcasm is not easy to match, as follows

The greatest slink that ever slank,

For burning Houses and stealing Sheep,

He fairly makes for to weep.”

It was his habit to jot down anything- which came into his mind on a slate, which he had hanging in his kitchen Thus he would write down n a short poem or an epigram while he was cooking his breakfast, and retail his happy thoughts to his workmates at snack, or he would elaborate them later at his leisure.

He was tender in his feelings for his fellow men, and especially was he a great lover of children and animals. Not only did he write poems on both of these subjects, but they are constantly referred to in many of his writings as an infallible index to a writer’s real nature.

He was very poor all his life. In a measure, this was due to his restlessness – which his wife shared with him. He could not settle down n anywhere here and was constantly changing his quarters in less than in seventeen years he lived in seventeen different houses. He emigrated to the States, but found that he had been deceived by the emigration agent and soon returned with his tail between his legs. To justify himself apparently he wrote and circulated a description of his experiences still extant, which is a terrible indictment of which was allowed on board the passenger sailing vessels in the year 1857. For a short while he worked as a miner in the Durham Coal Field, but he missed his old home on the Hill and came back, when he built himself a cottage enjoying one of the most charming views of moor and dale one can find on the Hill, but he was obliged to dispose of it, as his financial position became strained.

He was keen on his work as a miner, but a somewhat speculative one In those days the mining companies used to let off portions of the mine workings to private parties, and there was keen competition at times for likely ”spots,” which were thought to have good prospects of repaying the labour expended in producing the cleaned ore. Such places or, as they were called, “bargains”, because different parties competing bargained with the Mine Agent for the privilege to work the places, varied considerably. The party which made the lowest bid per “bing” of dressed ore would have the right to work the bargain for a month. Thomas Blackah was always optimistic, so he seldom benefited proportionally to the work required.

He must have been a cool-headed man, where his work was concerned, as an experience he once had shows. One Sunday morning without saying anything to anybody he took a bunch of candles, hung them by their wicks on his collar button and went off to explore an old abandoned mine, about which the usual legend was told, that it was really rich, but that the company which had sunk the shaft and driven the levels had missed the mark. Thomas climbed down the old rotten ladders, which were still there, but in stepping on to the top rung a twig of a bush growing on the shaft edge, unseen by him, lifted the bunch of candles off his collar button. Fortunately for Thomas, they remained suspended on the twig.

Arriving at the bottom of the. shaft, Thomas Blackah, as old miners usually did to save their precious candles, set off from the shaft foot without bothering to light a candle. After walking for some distance – the echo told him that he had arrived at a place where there were other workings – he discovered when he tried to light a candle that they were gone, as well as his matches. Believing that they had dropped down where he stood, he began seeking about the floor but found nothing. In seeking he had lost his bearings and realizing the seriousness of his position, as he was as likely to move away from the shaft foot and might walk into open or running ground, as be was to retrace his steps, he selected as dry a spot as he could find by feeling, sat down and patiently waited until he would be discovered by his mates, which he was the next day. Search parties had been combing the moors looking for him fortunately, somebody spotted the bunch of candles, which gave the clue to his whereabouts, and he was rescued from his unenviable position.

I will mention one more incident illustrating the character of this generous-hearted man. When “Boney” was on the go and the Luddite risings took place in the West Riding and Lancashire, a company of soldiers was marched from York across the Hill on a very hot day, and one of the soldiers fell out ‘and died on the roadside. The men were halted and quartered for the night in the village so that necessary arrangements could be made and the poor soldier lad was buried the next day with honours of where he fell. Such was the story related by the old men in later years. Many did not believe it, though a mound on the roadside on Coldstones was always referred to ‘is ”John Kay’s Greeave”. On one occasion when the incident was discussed at the ”Miners’ Arms,” doubt was again thrown on the truth of the incident. Thomas Blackah, who hid heard the story when a boy, also doubted it, but suggested they should open the mound and see for themselves, for ”we have picks and shovels ‘and we can soon we can make sure”, as he said. This suggestion was acted on, and Blackah gave a helping hand. Four or five feet down they came across some bones, a skull, part of an old flintlock ‘and some other pieces of iron which all testified to the truth of the story. Thomas Blackah was very upset by what he considered was tantamount to sacrilege and he did all he could to restore everything as it was and set up two stones to mark the place. These stones can still be seen standing opposite Coldstones Pond. He also carved in the roof of Gillfield Level, which happens to pass directly below the place, a coffin and the name of John Kay to atone for, what he looked on as a crime against a fellow man. I have these details from three persons, one a woman, who were present. They all three had noticed and remembered the change that came over Thomas, from flippant hilarity to grave solemnity, when they found the remains of the unfortunate soldier boy, who up till then had rested peacefully in his lonely grave.

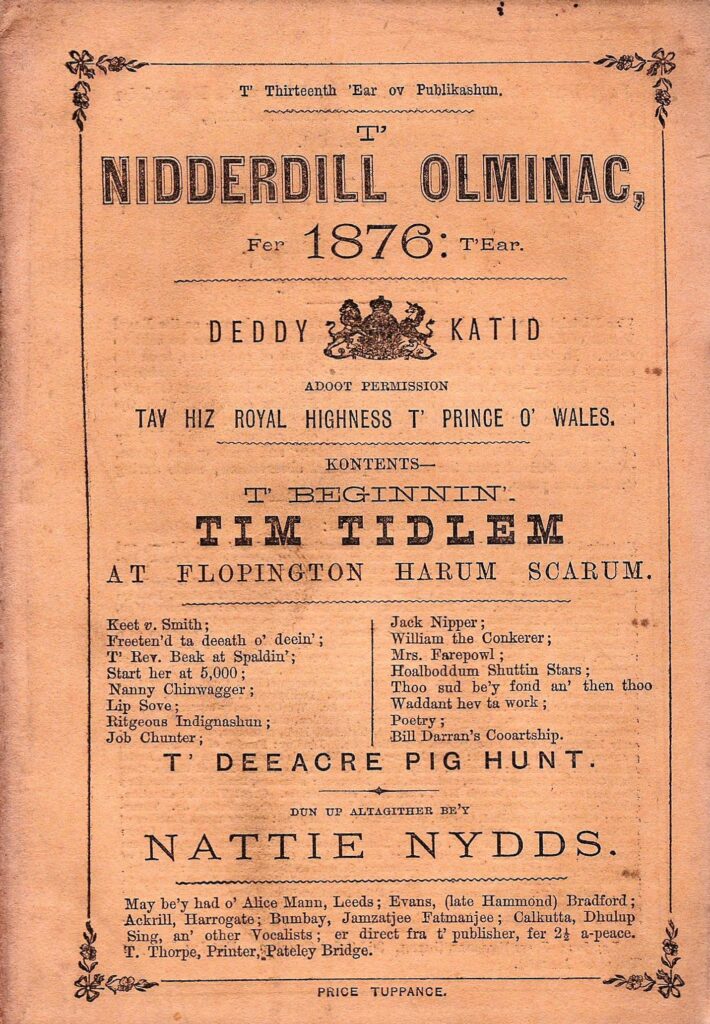

He was a constant contributor to the local papers some of his prize poems he had printed and sold for a few pence. A collection of his poems was published under the title “Songs and Poems” in 1867. Some of these were in English, but the majority were in dialect. He also wrote and published for some years a dialect almanac, ”T’ Nidderdill Olminac,” under the pseudonym of “Natty Nydds.”

His almanac publications were all written in a humorous strain, and as they abounded with pointed references to known persons by name or nickname, they were very much appreciated by the Up and Down Dalers. I have met some of his contemporaries, who nearly all could recite, not only his poems, but also long prose pieces, this because the latter were mostly written round actual happenings. Moreover, he wrote about the villagers themselves, their wives, sweethearts, bairns and their humble houses, truthfully but with the sentimental outlook which so greatly appeals to them and, moreover, in their own homely dialect. As a consequence he was well known and appreciated amongst the men of the mines and the mills of the North, the editions of his almanacs reaching into the thousands. Though at one time so highly prized, his writings are now by no means easy to come across, this partly because they are now jealously guarded by their owners, and partly because, being sold at such low prices, they were not at the time valued by those whose literary taste was influenced by the shoddy sentimentality and the thrillers of his time and consequently have been lost or destroyed.

His almanac publications were all written in a humorous strain, and as they abounded with pointed references to known persons by name or nickname, they were very much appreciated by the Up and Down Dalers. I have met some of his contemporaries, who nearly all could recite, not only his poems, but also long prose pieces, this because the latter were mostly written round actual happenings. Moreover, he wrote about the villagers themselves, their wives, sweethearts, bairns and their humble houses, truthfully but with the sentimental outlook which so greatly appeals to them and, moreover, in their own homely dialect. As a consequence he was well known and appreciated amongst the men of the mines and the mills of the North, the editions of his almanacs reaching into the thousands. Though at one time so highly prized, his writings are now by no means easy to come across, this partly because they are now jealously guarded by their owners, and partly because, being sold at such low prices, they were not at the time valued by those whose literary taste was influenced by the shoddy sentimentality and the thrillers of his time and consequently have been lost or destroyed.

As his dialect works represent probably the purest version of any Yorkshire dialects published, they are from this point of view the most valuable of his writings. It is for the purpose of trying to revive the interest of Yorkshire folk in the writings of one of the truest and best of their fellow countrymen and of the homely doric of their forebears, which the writer has learnt to love so well, but now in dire straits to hold its own against board schools, wireless, pictures and the closer contact with those who speak the nondescript language of the towns due to bikes and motors, that this little book sees the day. It has not been possible for the writer to examine all that he wrote and published, which as it is, is only a fraction of what he did write. For lack of means, time and opportunities he was only able to publish random writings.

One point should be noted in connection with his writings, which is how the spelling of the same word varies in his writings. One of the reasons for this is the difficulty he had, being an untrained phonetician, in determining the exact equivalent sound value of peculiar pronunciations in terms of the -accepted value of the letters of the alphabet A difficulty which lie shares with many other writers.

Besides writing poetry in his. spare time, he also used to knit woollen socks, scarves, gloves and the like, which he sold, having converted his front room into a kind of shop, where he also sold other kinds of useful things, such as stationery and the like, as well as his published writings. He used to sit in his shop knitting, while his friends and cronies would drop in for a crack. Having travelled and read so much, he naturally was a source of information; highly appreciated on the Hill, cut off as it was in those days to an extent which it is difficult to estimate to-day.

When the price of lead sank to such a disastrously low price as it did in the ‘eighties, the Greenhow Mines, like the majority of lead mines in England, were shut down, causing untold misery and poverty amongst the poorly paid workers of the lead mining centres of Yorkshire, who had to seek work wherever they could find it. Many of the Greenhow and Hardcastle families went to Leeds and Bradford in search of employment amongst these the Blackah family found their way to Leeds, where many of them are still to be found, and where many of them have reached safe and comfortable positions. The Blackah family were all very musical. The members of the family – there were six brothers – all played different instruments, and formed a band of considerable merit, much sought after on festive occasions in the neighbourhood. Thomas played the French horn.

Thomas Blackah was born at Hardcastle, a small, now deserted village near Greenhow Hill, on April 27th, 1828. He died in Leeds on March 10th, 1895, and is buried in Woodhouse Cemetery, Leeds.

The writer wishes to thank all those who have helped him in the labour of producing this little volume, and especially the. modern representatives of the Blackah family, who have so kindly supplied him with personal data about their gifted kinsman, and who have also assisted financially towards the publication of this book, as their contribution towards the newly built village Hall on Greenhow Hill, and also to keep the memory of him green in his village, which may be justly proud of their long departed fellow villager, who sang so sweetly about themselves and their homes.

H. J. L. BRUFF.

Kell House,

Greenhow Hill

July 1937

5 generations of Blackey/Blackah from Thomas Blackey 1711-1781 as either a chart or text

My Great great grandfather Richard was brother to Joseph. I was brought up in Shipley and now live in New Zealand. I would love to hear from any Blackah relatives.

I am related to the Blackah arm of the family that came from Portsmouth (Hampshire).

My two children live in New Zealand In Waiuku and Auckland.

I am a great grand daughter of Richard Blackah and would love to make contact with any other descendants of Richard. Malcolm has my email address on his data base.

I think I’ve got this right. One of Thomas’s sons was another Thomas who married Jane Hodgson. One of their daughters was called Hilda who married Clarence. One of their daughters is Margaret – still living in Leeds, and one of her daughters is my wife Sue. We have the typed record of Thomas’s cross Atlantic journeys (more like a novella) and it will hopefully soon be turned into a PDF for ease of sharing with any interested parties.

Regards to all.

Terry Waller

Correct, his son Thomas Artemas Blackah married Jane Hodgson in Leeds in 1896. Their daughter Hilda (1901-1978) married Clarence Thorley in 1923 and their daughter Margaret b.1931 married Robert Kidd and they had a daughter called Susan.

Hi Terry. Do you know if Hilda had sisters? If so, could these be Ada & Ann? It’s possible there were more siblings, but these would be the ones I remember. I remember a Hilda, she lived in/near Lower Wortley in Leeds. Is this the same one?